This past election season, 82 percent of voters in Golden, Colorado said “yes” to a ballot initiative that authorized the town’s city council to make way for a new community solar garden. More residents voted on the solar question than those who voted to elect their city councilors

Granted, along with some 18,000 residents, Golden is home to the National Renewable Energy Lab (NREL), the Energy Department’s leading solar research facility. Still, the popularity of community solar is high and growing.

According to the most recent numbers from the Smart Electric Power Alliance (SEPA), there are 183 utility-led community solar programs in the U.S. with nearly 380 megawatts of installed capacity. Two thirds of that capacity comes from 22 investor-owned utility programs. The rest comes from 30 municipal utilities – which have 41 megawatts installed – and 131 rural electric cooperatives, which SEPA estimates to be managing some 80 megawatts of capacity.

SEPA Utility Strategy Manager Dan Chwastyk told Utility Dive that “There are also 848 megawatts of announced projects in the pipeline, showing a clear growth trend.” GTM Research agrees. Its analysts predict community solar could become a 500-megawatt annual market by 2019.

The sharing energy economy

Uber and Lyft made it OK to share cars. Airbnb got us sharing our homes. Community solar has us sharing our green power generation.

Paul Zummo, director of policy research and analysis at the American Public Power Association (APPA), has a succinct definition of community solar: “It’s a facility that allows multiple users to purchase generation from a solar array located offsite,” he says. “Generally, the community solar project is larger-scale – not utility-scale – and it’s located somewhere in the utility service territory.”

Zummo also explains the two primary business models under which utilities offer participation in community solar. Either consumers lease a share of the power generated and pay a small amount each month, or they purchase panels upfront and get recurring credits for their panels’ production.

In constructing community solar projects, public utilities and co-ops have a shared limitation: As non-profit organizations, neither qualifies for federal tax credits. For that reason, Zummo says it’s usually a third party that builds the installation and gives the utility discounted electricity that reflects tax credits, a savings the utility can pass along to consumers.

That’s pretty much how the Middle Tennessee Electric Membership Corporation (MTEMC), the Volunteer State’s largest co-op, completed its first community solar project. “We utilized the National Renewables Cooperative Organization to ensure we could reduce the overall cost and recognize the federal tax credit and other financial tools that make the project more economical,” says Brad Gibson, chief cooperative business officer for MTEMC.

His colleague, Electrical Engineer Avery Ashby, explains that such an arrangement is called an equity flip. “A tax equity partner owns a portion of the installation for several years, depreciates it and they flip it back to us.”

Meeting demand

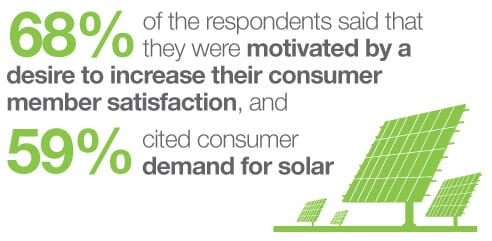

Why did MTEMC – and dozens of other co-ops – start offering community solar? Tracy Warren, senior communications manager for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association (NRECA), has results from a survey her association conducted with its membership. ” percent of the respondents said that they were motivated by a desire to increase their consumer member satisfaction, and 59 percent cited consumer demand for solar” as the driver, she says.

If all those consumers want solar power, why don’t they invest in a rooftop system? Warren points out that many can’t. NREL estimates that 50 percent of rooftops are inappropriate for solar systems for a variety of reasons. Either the resident is a renter, the roof has too much shading, the roof is oriented in the wrong direction, there’s a homeowner’s association that says “no” … it’s a long list. GTM Research also thinks it’s a higher number. According to them, 77 percent of U.S. residences are probably ineligible for rooftop solar.

Yet, people want to go green. “As a cooperative, we exist to serve the needs of our membership,” says MTEMC’s Gibson. “Increasing interest in solar was an opportunity for us to develop cooperative solar.”

Larry Taylor, the co-op’s engineering technology supervisor, adds, “It provides a low-cost entryway for our members to participate in renewable energy, and it demonstrates our ongoing dedication to sustainable development.”

MTEMC’s community solar program is open only to residential members, and they can purchase no more than two shares of the program. That’s a $20 monthly investment to have access to 5.5 panels of generation or 1.76 kilowatts of direct current, Gibson explains. Taylor adds: “In some months, generated capacity may be less than the monthly participation cost, and in some months, it may exceed that cost.” He says folks are likely to break even by the end of the year. Even if they don’t, they’re still gaining price breaks through the substantial economies of scale a community solar project delivers. What’s more, these customers skip the headaches of a rooftop installation.

Even without the savings, Ashby says MTEMC members are increasingly requesting such options. The co-op’s member-driven board of directors has approved more installations. Before they proceed, they’ll need approval from Tennessee Valley Authority, MTEMC’s generation and transmission provider.

Utility perks

Utility perks

Along with pleasing consumers, there are plenty of advantages for utilities that invest in community solar. One is price. “We get economies of scale,” says Ashby. “We’re purchasing 3,000 panels at once, so the cost per kilowatt goes down versus if a member were to do it.”

There’s also a control factor. “With our own field, if we need to turn it off because of over-voltage or control the inverters, we have the ability to do that,” Taylor says.

APPA’s Paul Zummo adds that having a central, utility-operated resource versus several small, customer-owned solar sites makes for easier system planning. It’s easier on the billing front, too. “Net metering has been a bone of contention. With community solar, you can set up the pricing in a way that’s more equitable for the utility and all its customers. The cost is borne by the people who are actually participating in the program,” he explains.

What’s more, some utilities are looking at ways to make community solar support their own systems. According to Utility Dive, “Sacramento Municipal Utility District (SMUD) is developing projects that will be paired with electric vehicle charging and grid services.”

Steele Waseca Cooperative Electric (SWCE) pairs subscriptions to its solar array with a free electric water heater if customers also participate in its demand response program. A SEPA study found that the utility reaps payback “through additional electric sales from the water heating and the savings on wholesale power costs by shifting purchases dedicated to water heating to off-peak hours.”

Sunny-side up

NRECA’s Tracy Warren anticipates that community solar will continue to be popular for cooperatives because it offers a way to engage members. According to NRECA research, as many as 40 percent of co-op members are “going to be supportive” of community solar initiatives, she says, although she adds that “there’s a big gap between being generally supportive and wanting to pay extra for solar energy.”

Still, NRECA has taken a little of the risk out of community solar for its co-op members. As part of the Energy Department’s SunShot initiative, the association has put together comprehensive how-to materials to help co-op leaders go green.

“We put together manuals for engineers, financial screening tools for the money people at co-ops, a marketing toolbox for the communicators. We addressed every piece of a community solar project so that co-op people would feel like solar was a do-able thing,” Warren explains. “What we found was that we then had a quadrupling of the solar capacity, and it was made available largely through these community solar projects.”

Warren adds that community “fits with a lot of co-op principles” of serving members and giving them what they want.

Looking at a recent opinion poll, that could be said for any utility.

This past July, the Danish clean-energy company Ørsted surveyed 26,000 people in 13 countries and found that 83 percent of those in the U.S. think it’s important to create a world fully powered by renewables. The U.S. score is tied with Denmark and France, trails Germany and Canada by one percentage point and tops the U.K. by one point as well.

Clearly, if it wound up on the ballot in most communities, renewable energy would likely win the “yes” vote.